Musings on Paleolithic Art and Consciousness

I’m actually somewhat uncomfortable calling Paleolithic renderings “art” – not because they don’t meet some standard set of criterion, but because of the very nature of the ‘calling’ itself seems to go against the experience of the makers of the art. See, there again, an assumption: “the makers of the art”, which includes a dichotomy between the producer and the produced. Our modern language is so full of this type of construction that it is almost impossible to get away from, or to recognize its influence on the content and method of our thinking – which is particularly problematic (at least if unrecognized) when we attempt to consider something like the inner experience of the people in the cultures which produced the images on the rock walls so long ago.

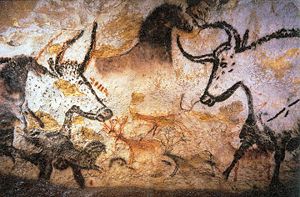

Van James, in his book Spirit and Art, paints a picture (in the consciousness of the reader) of the process by which the art was created, including its cultural context, indicating that it had to do with a shift from participatory consciousness to one that had the seeds of self-recognition, and thus self-abstraction, as an essential component. I find this interesting because many artists throughout history, including today, mention something about the way in which one gets lost in the process of creating. This experience of the space between “me” and “my art” asymptotically approaches zero, leaving the artist with an experience of creation without “A” creator. Only retrospectively may an artist whose creating occurs in this state attribute the work rationally to some specific time period, place, and personality; but this knowledge does not need to be held in consciousness during the actual process of creation itself, and (as many artists know) may actively interfere with what might otherwise be brought forth.

So I wonder if this experience – or LACK of experience, as the case may be – which characterizes some part of the process of artistic creation even today, may be something that was the ‘cutting edge’ of consciousness in the Paleolithic period. Jean Gebser’s “magic structure” (cf. The Everpresent Origin) speaks of this in a way similar to that of Van James, indicating that the art of this period was indicative of human beings waking up to themselves. Before this stage, (Gebser’s “archaic”), it is not possible to really speak of art at all, of creations “of” humans, because the consciousness was in identity with the world. It is only by transitioning to a consciousness of “unity” that art even becomes possible, because in “unity” is already contained the indication of multiplicity, as multiplicity is required in order for unity to be brought about (otherwise one simply has identity). Thus Paleolithic art may exemplify this transition in consciousness from identity to unity, which gives expression to sensory and magical experience in a form that takes this experience even further, strengthening it recursively through the very act of its creation. The painting of animals, of human figures, and of stenciled human hands may serve as a ‘catch’ for consciousness, by which it can step outside its mode of identity (akin to dreamless sleep) and into a mode which recognizes the beginning of division between the human being and the world (akin to dreaming sleep).

So perhaps the pictures of animals and such on the cave walls are not really pictures “of”, but are rather more like techniques for transforming consciousness. We moderns are taught to pay more attention to things rather than processes, so we tend to see the results of some activity as the most important ‘thing’ to consider, i.e. the art itself. But maybe this was not always the case; maybe Paleolithic art was ‘something’ primarily in its making, in the process of its unfolding (such as in Tibetan sand mandalas, or Native American healing mandalas), and not so much in its product, the image on the wall. But, recursively, the production of the images may lead one who views it but does not create it, into a different space of consciousness – a space which invites both a ‘connection to’ and a ‘disconnection from’ at the same time. Maybe the Paleolithic viewer of Paleolithic art was both put into connection with the cultural significance of the art in an experience of magical unity with the forces identified by the culture, while also being called to experience the art in a way that called forth something from within that necessitated a concurrent experience of the without. The very experience of one’s unity with the world perhaps awakened the first seeds of dis-unity, of separation between what would eventually be one’s “self” and “the world”.

Interesting article – thanks